Hi folks,

I once worked with a friend who quoted The Big Lebowsky like it was his job. And when I admitted that I hadn’t seen it more than 10 years after its release, he pressured me into watching it. I did, and I thought it was merely /okay/.

My friend was offended by my atrocious taste.

But it wasn’t my taste that was bad (this time) – it was that the world had moved on and the movie no longer felt fresh and new, even to somebody who hadn’t seen it. It’s the same way that my 6 year old daughter can hear a song by Cab Calloway and know “this is an old song.” Minnie the Moocher might be a great classic, but it’s obvious that it doesn’t fit into the current context.

When we’re communicating – whether it’s via a movie, music, or (more likely for all of us) via an email or presentation or discussion – timing is critical. You could have the right message, the right person to deliver it, and the right audience, but if your timing isn’t right, you’re unlikely to succeed.

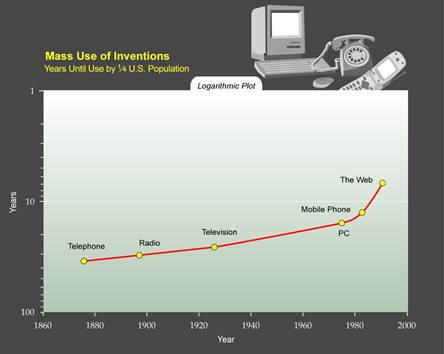

It’s the same concept described in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers – that many of the extraordinarily successful individuals in our society are successful, in large part, due to the timing of their birth. Had their natural brilliance, ambition, and drive not intersected with the right timing, we’d have never heard of Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and countless others.

Timing may not be everything, but it’s a big chunk of everything.

A great example of this is in the 1957 classic, 12 Angry Men. [spoiler alert] In the movie, juror #8 argues that the evidence presented against a young man in a murder case is insufficient to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. At a key moment, after spending nearly 30 minutes trying to convince his fellow jurors of his perspective, he pulls from his pocket his strongest evidence – a knife identical to the “unique” knife used in the murder. It’s the turning point in the story – the point from where he’s able to eventually convince all of his fellow jurors of his perspective.

The question for all of us is; how long could we keep the knife in our pocket? Will we be overly anxious and show the knife too early? Or will we withhold it too long and let the right moment pass us by? Do we have the patience and sense of timing to only reveal our best evidence when it is most likely to resonate?

Rex