Hi folks,

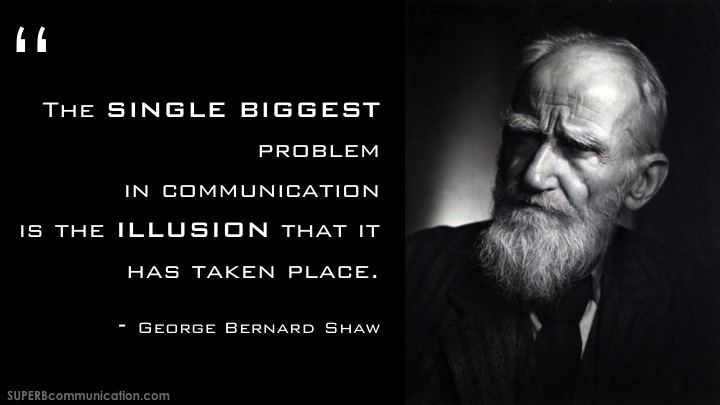

One of my favorite quotes on communications is by George Bernard Shaw, the Irish dramatist and critic, Nobel Laureate, Academy Award winner – just a general big brain kind of guy.

I think this gets to the heart of the issue with communications – all too frequently, one or more parties are operating under the assumption that effective communication has occurred when, in fact, it hasn’t.

There are an unlimited number of examples of this, but I’ll focus on just one tragic one.

In 1162, Thomas Becket was serving as Lord Chancellor to King Henry II of England. When the position of Archbishop of Canterbury – the highest church position in England – opened up, Henry appointed Becket, thinking he would prioritize the needs of the state above those of the church. Henry was soon disappointed, though, and Becket almost immediately resigned as Chancellor and became a serious thorn in Henry’s side as he agitated for stronger church power at the expense of Henry’s state.

In 1170, the feud came to a head when Becket excommunicated a bunch of Henry’s allies during their latest squabble. Henry, at his height of frustration, lamented aloud “who will rid me of this troublesome priest?” A handful of knights overheard this and interpreted it as a royal command, mounted their horses, and headed for Canterbury. Once there, they hunted Becket down and, in the middle of the cathedral, murdered him.

Right. That wasn’t Henry’s intent. But because of his position, his words had an unintentional, outsized impact.

There are modern equivalents, too. Jeff Weiner is the CEO of LinkedIn. Years ago, he got wind that his casual comments were having a big, unintended impact – direct reports would scramble to address what they thought were commands when he was actually only expressing an opinion. It was wasting precious time and energy, so Jeff came up with a plan. He implemented a three-tiered structure for his feedback – it would be categorized as either one person’s opinion, a strong suggestion, or a mandate. This helped clarify the weight his words should carry and thereby eliminate that wasted effort people spent trying to carry out imagined commands.

Now, most of us aren’t kings or CEOs, but we still have to be mindful of the impact of our words – especially folks who are in positions of authority. What we say can carry significant weight – often time more than needed or intended. If we have good people around us, we want to make sure we’re getting the most out of their expertise and judgment, not just getting copies of a single person’s (read:our) vision and opinions. Just like King Henry or Jeff Weiner, we all need to understand how our words carry weight and we need to choose them carefully.

Rex