Hi folks,

I have yet to get into the whole cryptocurrency thing. It’s clearly an awesome concept with all sorts of implications (good and bad) for individuals and society writ large, but I just haven’t had a motivation to buy into it. Maybe I should be buying more narcotics online, I don’t know…

Anyhow, the ideal time to have gotten into bitcoin was seven years ago, when the currency first emerged. That’s when Kristoffer Koch got into it, buying around $26 worth of bitcoin as part of some academic research. He forgot about them for four years at which point they had become worth around $1 million. If he still hung onto them until today, they’d now be worth more than twice that.

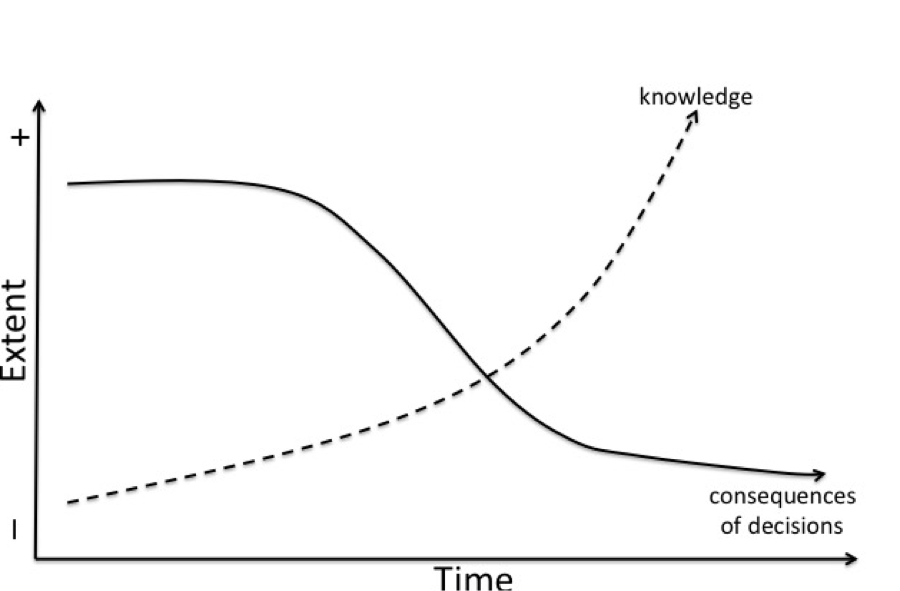

Koch clearly didn’t know that was going to happen – he made a relatively blind investment. Had he waited until he had better information – until he saw the appreciation of bitcoin value, his $26 wouldn’t have yielded nearly the return that it did.

That’s the point of the consequences model developed by Danish organizational theorists Kristian Kreiner and Søren Christiansen. They argue that the greatest opportunity for impact is at the beginning of any timeline – precisely when you have the least knowledge. Yes, you’re making decisions with minimal information, but if you’re looking to have a big impact, you need to be comfortable operating without perfect knowledge. Wait too long for the knowledge you need in order to be sure you’re making the right move, and you’ll lose your chance for that big impact.

But that big impact could be good or it could be bad, and that uncertainty paralyzes many, many people.

In security, we often don’t have the luxury of waiting for perfect information. Whether it’s responding to an attack, fixing a known vulnerability, or choosing a new defensive technology, any delay in our decision works to the advantage of the bad guys.

So how do we handle this? I’d argue the most effective is to push that knowledge curve to the left. How? By better preparing for expected scenarios. Suspect you’re going to have an incident where you need to determine the nature of the impacted assets? Then don’t wait until an incident to figure out what applications a system is supporting – develop that knowledge in advance through an asset inventory and make it available to your Ops team. Know that vulnerabilities are going to be uncovered in operating systems and software over time? Then improve your patching process to allow for rapid deployment of critical fixes. Think you’ll need a new IPS next year? Then start the research now well before it’s time to make the investment decision.

Better preparation allows quicker AND better informed decisions. Will we still have to make decisions without perfect knowledge? Yes. Should security professionals get comfortable with that? Absolutely. But we’re not helpless – we can push that knowledge curve to the left and help our future selves by investing some effort to develop knowledge today, before it’s needed.

That, too.

Rex