Hi folks,

Spring is here in Washington DC, which means the arrival of massive hordes trying to time their visit with the peak for cherry blossoms at the tidal basin. Which I get, because at their peak, they look like:

Thankfully the influx of people gives us locals a great opportunity to get indignant about idling buses, people who don’t understand escalator rules, and inconvenient crowds who dare visit our amazing city to appreciate what we take for granted year-round.

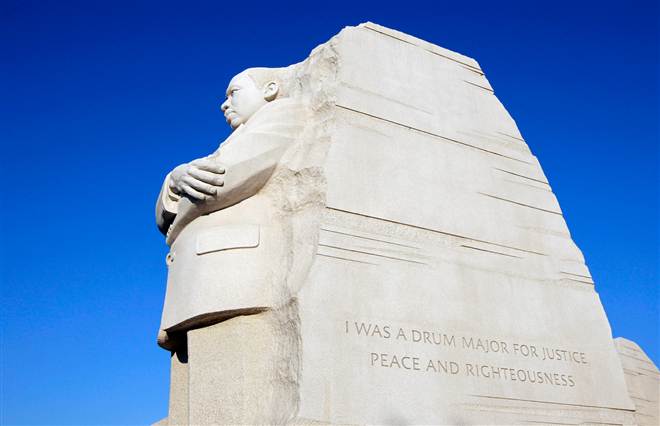

The newest monument the crowds will be visiting is the Martin Luther King memorial on the tidal basin. Visitors will read a number of inspiring quotes from Dr. King on the side of the massive sculpture. One quote that they won’t read?

I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness.

That’s because he never said those words. But they were on the monument when it was first unveiled:

What he actually said – in a speech predicting his own eulogy just 2 months before his assassination – was:

Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice, say that I was a drum major for peace, I was a drum major for righteousness, and all the other shallow things will not matter.

Pretty different, huh? As Maya Angelou said, the abbreviated version makes King “look like an arrogant twit… It makes him seem less than the humanitarian he was. . . . It makes him seem an egotist.” It totally mangled the context of the original. The paraphrase was removed from the monument.

What does this have to do with work matters?

In the strategic security field, we’re frequently required to combine multiple abstract frameworks, align their various components, and distill them into understandable, actionable requirements for others in our organization to follow. Consider the risk management framework. There’s at least a half-dozen concepts converging in a single, umbrella effort. Each concept has its own levels of abstractness and tactical requirements and they all must fit together in an orderly, reasonable fashion. And since NIST is smart enough to avoid being overly prescriptive with this framework and the components, each agency needs to figure this out for themselves.

It’s not easy. We’ve unfortunately confused people from day 1 about our approach and we’re still struggling to get it right.

When we communicate, there are a handful of principles we should always follow. The one I want to touch upon today is providing the context.

Just like the quote on the King monument, the story around your communication matters. This is different than the meta, theories of communication kind of context. This is simply explaining the “why am I communicating / what am I communicating about” as the first thing you do upon initiating a communication.

And this isn’t important only so people don’t misconstrue the meaning of your words. A 2006 study found that professionals change their tasks about every 3 minutes and they switch across about 12 projects, or “working spheres.” We’re all distracted with too much on our minds. If you’re trying to insert communication into somebody’s brain, some nice introductory context helps ease the transition. Never assume the reader or listener is already on the same page, ready to receive your message. Chances are they’re not. Getting them there ASAP increases the chance that your message will be received as intended.

Rex